[Note: This post links with a sermon of mine, which can be found here.]

Introducing the Problem

One of the primary claims of the Christian faith is, “Jesus is Lord.” This is an exclusive claim. It not only means that, “Krishna isn’t Lord” and “Allah isn’t Lord,” and “Buddha isn’t Lord,” but also that no ruler (e.g. King, President, or Prime Minister, etc.) or nation (e.g. India, USA, UK, etc.) can claim the ultimate allegiance of a Christian.

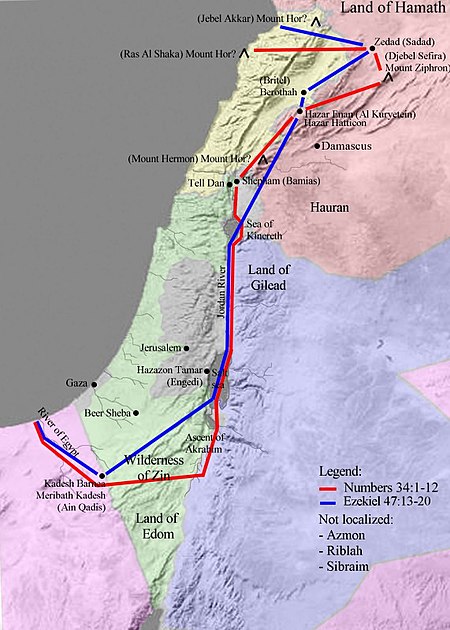

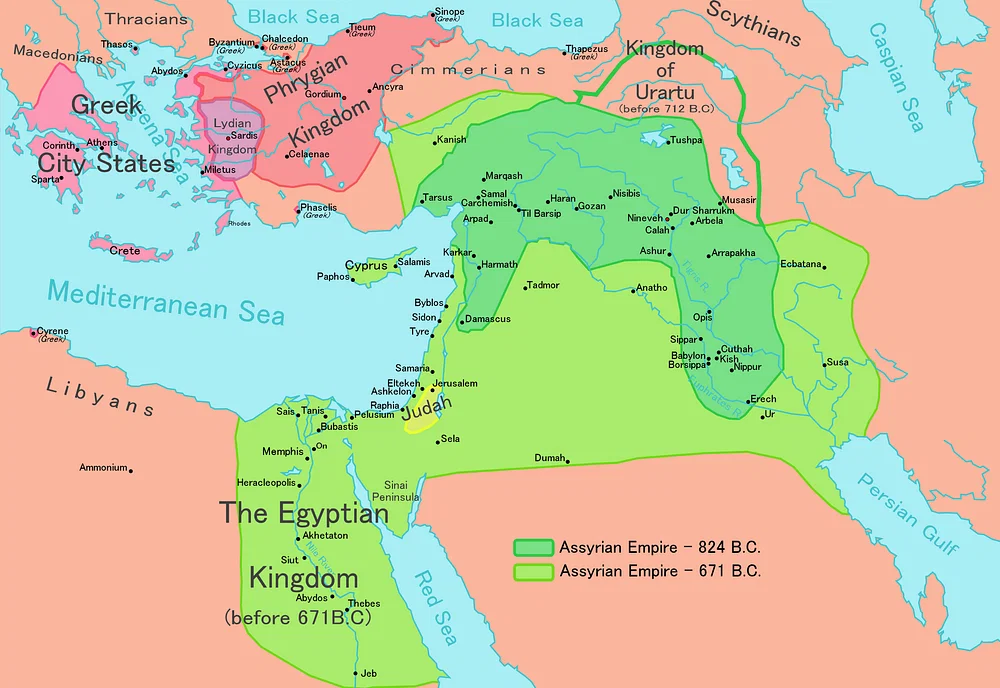

However, if Jesus is Lord of the whole world, then why was the revelation that came through him given to the Jewish people in the province of Palestine in the first century during the reigns of Augustus and Tiberius? In other words, if I claim that Jesus’ lordship extends to the whole world through time, why did God not give this revelation in creation itself so that everyone could clearly see it and believe? Why was it given in specific historical, geographical, cultural, and linguistic contexts? I will discuss this from six related and developing perspectives.

Denial of Reality

Suppose, for example, that what God wanted to tell us, including especially the revelation we receive about God through Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection, was universally available to all people, in all places, and at all times. I would just have to be an honest seeker and wake up one morning with the determination that I wanted to learn about God. Then I could, on the one hand, ask some expert for the insights she had concerning God and how she came upon these insights. Since everything is available without any obstruction, this expert would just have to indicate the evidence she found convincing and I would be convinced about these truths because they would now be universally available. Or I could, on the other hand, undertake a journey of discovery on my own and reach similar conclusions.

Note that for something to be universally available, it would have to be something that did not rely on any superior intellect or specially tuned senses. Otherwise, it would automatically be not universally available. So right away we can exclude things like any of the laws or theories that are used in the natural sciences. Einstein’s theory of gravitation, for example, while being the prevailing scientific wisdom today, was not known a little over a century ago. Hence, in the 19th century, this wisdom, while universally available, was not universally accessible because human knowledge had not progressed to a level where this new insight was needed. We could extend this to all developments of human knowledge, from the area of geometry, codified for us by Euclid, to the area of psychology, theorized by Freud, Jung, and others.

In other words, to say that knowledge about God had to be universally available would mean that such knowledge would have to be at the level of the sunrise and sunset or the phases of the moon or the constellation of stars. These phenomena are universally available. Note that even a phenomenon like the tides could not count for there are vast regions in the earth’s land mass where people do not have access to the tides. However, even the behavior of the sun, moon, and stars would not suffice. The sun’s behavior differs in the northern and southern hemispheres. The moon’s phases differ, even if slightly, with longitude. And the constellations in the southern hemisphere do not appear in the northern hemisphere and vice versa.

In other words, there is actually no natural phenomenon that can be understood by almost every human and that still is universally accessible by every human. Hence, any assertion that knowledge about God must be universally available to all humans is based on a denial of reality itself, for the reality is that our experiences of the natural world depend, in large part, on where we find ourselves on this earth.

Divine Action in History

But let us assume that there is some phenomenon that is universally available and accessible by all humans. The natural phenomena that come closest to this universal ideal are the rising and setting of the sun and the changing of the phases of the moon. This is why almost all cultures have calendars based on solar or lunar activity, the former centering around the solstices and the equinoxes and the latter centering around the new, quarter, or full moon phases.

While these solar and lunar phenomena are excellent as the bases of calendars, they do not allow for historical progression. Today’s sunrise is much the same as yesterday’s and both will be the same as tomorrow’s. This cycle’s new moon is much the same as the previous new moon and both will be the same as the next new moon. While our calendars may indicate that we have some festival to observe, and while we may mark some historical event based on the solar and lunar phenomena that coincided with the event, the solar and lunar cycles themselves do not constitute history.

In fact, it is precisely because they are so universally available and accessible, due to which we are able to mark our calendars using them, that they, ironically, do not themselves provide any historical development. What this means is that the more widely available and accessible some phenomenon is, the less likely it can be used as a marker of a historical event.

Hence, if we insist that the creator God is in a relationship with his creation and acts within it, he cannot do it through commonly available and accessible phenomena. If we saw the sea parting everyday, as described in Exodus, it would not be of any significance but would be rendered as yet another ho-hum natural event that we take for granted. Hence, for God’s actions to be historically significant, they cannot be universally available and accessible. Of course, we could say that we prefer things that are universally available and accessible. However, that would mean believing in a God who actually does not act in history. Since one of the foundational beliefs of the Christian faith is that God has acted in history, any view that proposes that knowledge of God is universally available and accessible has to be classified as sub-Christian or anti-Christian.

Storytelling and Embodiment

Now history is a record of the flow of time. When we say, for instance, that Abraham lived in the 2nd millennium BC and Jesus in the 1st century AD, we are placing Abraham and Jesus relative to each other – and to us – with respect to time. It would be disingenuous for us to expect Abraham to know things that were revealed only in, through, and by Jesus, a fact that far too many Christians fail to appreciate when they interpret the scriptures.

Since history is a record of the flow of time, history itself tells a story. If we read the books of the bible as though they were historical documents, and if we were able to arrange them in a roughly chronological order, we would be able to discern a story of God’s interactions with his creation. Now, quite obviously the books of the bible are not just historical books. They are books intended to teach the reader about God. But specifically, they are intended to teach the reader how God interacts with his human creatures. In other words, through the books of the bible, we are able to say that God interacts with us in certain ways and does not interact with us in certain other ways.

However, this is not given to us in propositional form since God’s interactions with humans are historically rooted. In other words, since God interacts with us in and through history, there cannot be universal propositions that dictate how God interacts with us, since the contexts each person finds herself in will be different from the ones in which the biblical characters found themselves.

What the historical narrative of the bible does is portray the lives of others like us. The bible does not whitewash their flaws and, hence, we are able to identify with these broken people through our own brokenness.

What would have happened if God had given us an ahistorical book (or collection of books) that spelled out a set of propositions to live by that were universally available to everyone? We don’t have to guess much here, but only have to look at what Christians who held such views did in the past. Invariably, a living relationship with God, in which God can surprise us and we can surprise God, is jettisoned in favor of a rigid legalism. After all, if I have a set of ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ why bother with a relationship? Relationships are messy and unpredictable. They have the potential to cause stress in our lives, especially when we want to please the other person but have no clue how to do that.

Laws, however, are easy. They may not be easy to follow. But they give us the impression that we at least know how we ought to behave. However, the clarity that laws provide is detrimental to the formation and deepening of any relationship, as anyone with strong friendships or a long lasting marriage would readily attest.

Moreover, universal propositions are a denial of how we engage with life. None of us lives our lives propositionally. Rather, we negotiate between what is good, better, and best, or bad, worse, and worst. Life rarely, if ever, presents us with alternatives that are clear. We have to struggle with the alternatives, attempting to decide, not what would be the best course of action for any generic disciple of Jesus, but for us. I know that my life situations are different from yours. I know that my priorities are different from yours. I know that my hopes for the rest of my life are different from yours. It would be foolish for either of us to think that the same advice would help both of us. In other words, an expectation of universal principles to follow is a denial of our historical rootedness. It is a denial of the fact that your story is different from mine.

Hence, to expect God to have given some ahistorical, universal set of principles that is accessible to everyone everywhere is to ask God to deal with us as disembodied creatures who do not actually have to live through time, in a certain place, and interacting with a unique set of people. In other words, any view that expects God to have given us revelation that is not bound by time, history, geography, culture, and language, is to expect a subhuman revelation because all humans are bound by time, history, geography, culture, and language. This is the result of our embodied nature. Each of us, due to our embodiedness, has a different story to tell. The recognition of our embodiedness, involves our commitment to the storied nature of our existence. And hence, a denial of the need for a historically rooted story from God is a denial of our essential nature as embodied creatures.

Invitation to Storytelling

Nevertheless, each of us does not just have a story that we keep as our own. Rather, recognizing how crucial to our identities our stories are, we invite others to tell their stories and to hear ours. We gather around fires to share episodes from our lives. We sit around a table and share anecdotes. In fact, this is what we normally call ‘evangelism’ is supposed to be. Evangelism is not the repeating of some ‘laws’ or ‘principles’, as many have unfortunately taken it to be, thereby despoiling it of its most potent attributes. Rather, evangelism is equivalent to saying, “I can tell you how God’s life and my life intersect and intertwine. Perhaps this will help you see how it is possible for God’s life and yours to intersect and intertwine.”

In other words, what we call ‘evangelism’ is supposed to be nothing but the mutual sharing of stories by two embodied creatures in the attempt to assess which story is more promising, more hope filled, more joy infused, and, therefore, more likely to be aligned with reality. Through this shared storytelling we tell the other person, “I have tasted Yahweh and have found him good. I think you will also find him good if you taste him. Want to know how?”

However, for the most part, at least for the past few decades, ‘evangelism’ has been eviscerated by reducing it to sets of ‘laws’. But you see, the most compelling truth is not that “God has a plan for my life.” If I remain isolated, with a ‘plan’ all for me, it is effectively unattractive. If it is a plan for me, then it will begin with me and end with me. If I will have a life spanning seventy years, then there is nothing attractive about telling me that there is a plan that also has a similar duration.

However, if my story can become an integral part of the story of God, then I can belong to something that predated me by millennia and that will postdate me by millennia. I know that I am still insignificant. But I can now be part of something much larger, something that transcends my short life. Like a piece in a jigsaw puzzle, my life may be small enough to be vanishingly unimportant in the large scheme of things. However, its absence will be noticed.

In other words, it is precisely by locating my story within the larger tapestry of God’s story that I ironically will find my purpose. This is perhaps part of what Jesus meant when he said, “For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it.” (Matthew 16.25) When we lose ourselves in his story, we ironically find our place in his story. However, if we choose an ‘unstoried’ existence, relying on disembodied ‘universal truths’, we actually discover that we are indeed insignificant.

This invitation to storytelling is unique. It depends on the person telling the story and the person hearing it. This is why Paul’s narratives about how Jesus confronted him are never the same. This is why each of the four Gospels presents their story of Jesus that is colored by their own priorities and perspectives.

Designation to Agency

However, if God communicates his story through us when we tell our story, this means that our storytelling is essential to the telling of God’s story. It is not enough to tell people that Jesus is Lord. We must also share how his Lordship has affected our lives. The crucial question is, “How have I changed on account of being a disciple of Jesus?” This means that I must not only be the one to keep a careful account of my story with God, but also that I must be ready to share this story with others.

This means that, when Jesus recruits me to be a participant in his story, he does so with the idea that I will help him recruit others. However, if what I learn from my relationship with Jesus is readily available without the need for any particular circumstances, then I am actually not needed in the process of sharing God’s story.

Many Christians have, indeed, reached such conclusions, saying that God could reach the whole world with the gospel without any human agents. But this is a denial of the nature and character of God, which is to share with his creatures. God doing the whole thing on his own renders meaningless the process of preaching by which he has determined to share his story with the rest of the world.

In other words, being an inherently sharing person, it is intrinsic to God’s nature that he would delegate some parts of the storytelling to his creatures. To not do so would be to go against his very nature. What I am saying is that the proclamation of my story within the story of God is a part of the agency God has given me on account of his very nature. I have the privilege and honor of telling God’s story with my story intertwined in it because God has an inherently sharing nature.

If this is true, then any expectation that God would reveal himself in universal ways, without the need for any story, is a repudiation of the time-bound agency that each of us possesses. I cannot but tell my story since it is the only story of which I am fully informed. But if knowledge of God is divorced from storytelling, since it is presumed to exist universally, then there is no story to tell – neither God’s nor mine – since there is no progression of events from conflict to resolution. If this is the case, then the only agency I have, which necessarily involves my time-bound existence and the unfolding of my story within time, becomes inconsequential at best and a hindrance at worst.

What this means is that the expectation of universal truths actually undermines human agency as God’s images, who are expected to represent God to humans, telling his overarching story to humans, and to represent humans to God, telling their story to him.

The Storytelling of Love

However, God not only asks humans to represent him, but actually loves humans, along with the rest of his good creation. Love, however, for embodied creatures, must make itself visible in and through time. If we expect universal ideas that are available to everyone all the times, then there would have been no need for Jesus and his supreme act of love – the cross. Hence, the suggestion that God should have given us universal principles that are available and accessible to all is a denial of the love demonstrated on the cross.

Love, of course, is highly specific. I have two daughters. And though I love them equally, I do not love them in the same way. They are different persons, who respond differently to the ways in which I show my love. But precisely because of this, I have a different journey of love with each of my daughters. To say that there should be some universally available body of knowledge or revelation that is accessible and available to everyone is to deny the uniqueness of each relationship.

The storytelling of love involves all the episodes that constitute the history of the love between two people. Each story may certainly have points of overlap with other stories because we are all human and share similar kinds of experiences. However, the sequence and set of episodes that define one bond of love will be quite unique from all others precisely because each of us is free to respond to the demonstrations of love in different ways. Hence, to expect there to be universal knowledge of God that anyone can access anytime is to expect God to relate to us as though we were automatons produced on an assembly line.

But more than this, it is actually impossible to love a time-bound human without that love also being time-bound. If someone intends to love me, then that person must love me – warts and all. And I have a different set of warts than anyone else! My past, including everything that has happened to me and everyone I have met, especially those particularly close to me, have a significant effect on how I respond to anything someone says to me now. For someone to love me, he/she must love this person who has these particular failings, developed over a lifetime.

Necessity of the Scandal

What we have seen is that it is impossible to have anything meaningful that affects a human that is not also specific to the person involved. Any human interaction inherently involves particulars that cannot be replicated without denying our human nature. In other words, the desire for universal truths or universal principles that are available and accessible to anyone at any time is based on a denial of our humanity itself.

Because of this, though the scandal of particularity might seem to be offensive, it is the only way in which a God who desires to demonstrate his love for his creation could act. For to act in ways that affect humans who have a spatio-temporal existence necessitates God’s acting in spatio-temporal ways. In other words, the only way by which God could have any meaningful relationships with us is for him to condescend to relate with us through the limitations of space and time. This involves revealing himself through a unique history that includes specific places and people, localities and languages, cultures and chronologies.

You must be logged in to post a comment.